Coming from ORM to Slick

Introduction

Slick is not an object-relational mapper (ORM) like Hibernate or other JPA-based products. Slick is a data persistence solution like ORMs and naturally shares some concepts, but it also has significant differences. This chapter explains the differences in order to help you get the best out of Slick and avoid confusion for those familiar with ORMs. We explain how Slick manages to avoid many of the problems often referred to as the object-relational impedance mismatch.

A good term to describe Slick is functional-relational mapper. Slick allows working with relational data much like with immutable collections and focuses on flexible query composition and strongly controlled side-effects. ORMs usually expose mutable object-graphs, use side-effects like read- and write-caches and hard-code support for anticipated use-cases like inheritance or relationships via association tables. Slick focuses on getting the best out of accessing a relational data store. ORMs focus on persisting an object-graph.

ORMs are a natural approach when using databases from object-oriented languages. They try to allow working with persisted object-graphs partly as if they were completely in memory. Objects can be modified, associations can be changed and the object graph can be traversed. In practice this is not exactly easy to achieve due to the so called object-relational impedance mismatch. It makes ORMs hard to implement and often complicated to use for more than simple cases and if performance matters. Slick in contrast does not expose an object-graph. It is inspired by SQL and the relational model and mostly just maps their concepts to the most closely corresponding, type-safe Scala features. Database queries are expressed using a restricted, immutable, purely-functional subset of Scala much like collections. Slick also offers first-class SQL support as an alternative.

In practice, ORMs often suffer from conceptual problems of what they try to achieve, from mere problems of the implementations and from mis-use, because of their complexity. In the following we look at many features of ORMs and what you would use with Slick instead. We’ll first look at how to work with the object graph. We then look at a series of particular features and use cases and how to handle them with Slick.

Configuration

Some ORMs use extensive configuration files. Slick is configured using small amounts of Scala code. You have to provide information about how to connect to the database and write or auto-generate a database schema description if you want Slick to type-check your queries. Everything else like relationship definitions beyond foreign keys are ordinary Scala code, which can use familiar abstraction methods for re-use.

Mapping configuration

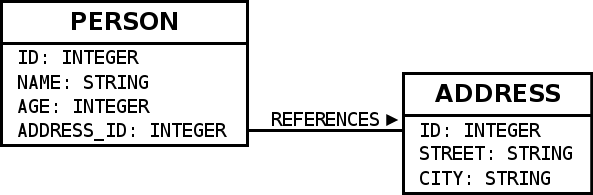

The later examples use the following database schema

mapped to Slick using the following code:

sourcetype Person = (Int,String,Int,Int)

class People(tag: Tag) extends Table[Person](tag, "PERSON") {

def id = column[Int]("ID", O.PrimaryKey, O.AutoInc)

def name = column[String]("NAME")

def age = column[Int]("AGE")

def addressId = column[Int]("ADDRESS_ID")

def * = (id,name,age,addressId)

def address = foreignKey("ADDRESS",addressId,addresses)(_.id)

}

lazy val people = TableQuery[People]

type Address = (Int,String,String)

class Addresses(tag: Tag) extends Table[Address](tag, "ADDRESS") {

def id = column[Int]("ID", O.PrimaryKey, O.AutoInc)

def street = column[String]("STREET")

def city = column[String]("CITY")

def * = (id,street,city)

}

lazy val addresses = TableQuery[Addresses]

Tables can alternatively be mapped to case classes. Similar code can be auto-generated or hand-written.

In ORMs you often provide your mapping specification in a configuration file. In Slick you provide it as Scala types like above, which are used to type-check Slick queries. A difference is that the Slick mapping is conceptually very simple. It only describes database tables and optionally maps rows to case classes or something else using arbitrary factories and extractors. It does contain information about foreign keys, but nothing else about relationships or other patterns. These are mapped using re-usable queries fragments instead.

Navigating the object graph

Using plain old method calls

This chapter could also be called strict vs. lazy or imperative vs. declarative. One common feature ORMs provide is using a persisted object graph just as if it was in-memory. And since it is not, artifacts like members or related objects are usually loaded ad-hoc only when they are needed. To make this happen, ORMs implement or intercept method calls, which look like they happen in-memory, but instead execute database queries as needed to return the desired results. Let’s look at an example using a hypothetical ORM:

sourceval people: Seq[Person] = PeopleFinder.getByIds(Seq(2,99,17,234))

val addresses: Seq[Address] = people.map(_.address)

How many database round trips does this require? In fact reasoning about this question for different code is one of the things you need to devote the most time to when learning the collections-like API of an ORM. What usually happens is, that the ORM would do an immediate database round trip for getByIds and return the resulting people. Then map would be a Scala List method and .map(_.address) accesses the address of each person. An ORM would witness the address accesses one-by-one not knowing upfront that they happen in a loop. This often leads to an additional database round trip for each person, which is not ideal (n+1 problem), because database round trips are expensive. To solve the problem, ORMs often provide means to work around this, by basically telling them about the future, so they can aggregate multiple upcoming round trips into fewer more efficient ones.

source // tell the ORM to load all related addresses at once

val people: Seq[Person] = PeopleFinder.getByIds(Seq(2,99,17,234)).prefetch(_.address)

val addresses: Seq[Address] = people.map(_.address)

Here the prefetch method instructs the hypothetical ORM to load all addresses immediately with the people, often in only one or two database round trips. The addresses are then stored in a cache many ORMs maintain. The later .map(_.address) call could then be fully served from the cache. Of course this is redundant as you basically need to provide the mapping to addresses twice and if you forget to prefetch you will have poor performance. How you specify the pre-fetching rules depends on the ORM, often using external configuration or inline like here.

Slick works differently. To do the same in Slick you would write the following. The type annotations are optional but shown here for clarity.

sourceval peopleQuery: Query[People,Person,Seq] = people.filter(_.id inSet(Set(2,99,17,234)))

val addressesQuery: Query[Addresses,Address,Seq] = peopleQuery.flatMap(_.address)

As we can see it looks very much like collection operations but the values we get are of type Query. They do not store results, only a plan of the operations that are needed to create a SQL query that produces the results when needed. No database round trips happen at all in our example. To actually fetch results, we have to compile the query to a database Action with .result and then run it on the Database.

sourceval addressesAction: DBIO[Seq[Address]] = addressesQuery.result

val addresses: Future[Seq[Address]] = db.run(addressesAction)

A single query is executed and the results returned. This makes database round trips very explicit and easy to reason about. Achieving few database round trips is easy.

As you can see with Slick we do not navigate the object graph (i.e. results) directly. We navigate it by composing queries instead, which are just place-holder values for potential database round trip yet to happen. We can lazily compose queries until they describe exactly what we need and then use a single Database.run call for execution.

Navigating the object graph directly in an ORM is problematic as explained earlier. Slick gets away without that feature. ORMs often solve the problem by offering a declarative query language as an alternative, which is similar to how you work with Slick.

Query languages

ORMs often come with declarative query languages like JPA’s JQL or Criteria API. Similar to SQL or Slick, they allow expressing queries yet to happen and make execution explicit.

String based embeddings

Quite commonly, these languages, for example HQL, but also SQL are embedded into programs as Strings. Here is an example for HQL.

sourceval hql: String = "FROM Person p WHERE p.id in (:ids)"

val q: Query = session.createQuery(hql)

q.setParameterList("ids", Array(2,99,17,234))

Strings are a very simple way to embed an arbitrary language and in many programming languages the only way without changing the compiler, for example in Java. While simple, this kind of embedding has significant limitations.

One issue is that tools often have no knowledge about the embedded language and treat queries as ordinary Strings. The compilers or interpreters of the host languages do not detect syntactical mistakes upfront or if the query produces a different type of result than expected. Also IDEs often do not provide syntax highlighting, code completion, inline error hints, etc.

More importantly, re-use is very hard. You would need to compose Strings in order to re-use certain parts of queries. As an exercise, try to make the id filtering part of our above HQL example re-useable, so we can use it for table person as well as address. It is really cumbersome.

In Java and many other languages, strings are the only way to embed a concise query language. As we will see in the next sections, Scala is more flexible.

Method based APIs

Instead of getting the ultimate flexibility for the embedded language, an alternative approach is to go with the extensibility features of the host language and use those. Object-oriented languages like Java and Scala allow extensibility through the definition of APIs consisting of objects and methods. JPA’s Criteria API use this concept and so does Slick. This allows the host language tools to partially understand the embedded language and provide better support for the features mentioned earlier. Here is an example using Criteria Queries.

sourceval id = Property.forName("id")

val q = session.createCriteria(classOf[Person])

.add( id in Array(2,99,17,234) )

A method based embedding makes queries compositional. Factoring out filtering by ids becomes easy:

sourcedef byIds(c: Criteria, ids: Array[Int]) = c.add( id in ids )

val c = byIds(

session.createCriteria(classOf[Person]),

Array(2,99,17,234)

)

Of course ids are a trivial example, but this becomes very useful for more complex queries.

Java APIs like JPA’s Criteria API do not use Scala’s operator overloading capabilities. This can lead to more cumbersome and less familiar code when expressing queries. Let’s query for all people younger 5 or older than 65 for example.

sourceval age = Property.forName("age")

val q = session.createCriteria(classOf[Person])

.add(

Restrictions.disjunction

.add(age lt 5)

.add(age gt 65)

)

With Scala’s operator overloading we can do better and that’s what Slick uses. Queries are very concise. The same query in Slick would look like this:

sourceval q = people.filter(p => p.age < 5 || p.age > 65)

There are some limitations to Scala’s overloading capabilities that affect Slick. In queries, one has to use === instead of ==, =!= instead of != and ++ for string concatenation instead of +. Also it is not possible to overload if expressions in Scala. Instead Slick comes with a small DSL for SQL case expressions.

As already mentioned, we are working with placeholder values, merely describing the query, not executing it. Here’s the same expression again with added type annotations to allow us looking behind the scenes a bit:

sourceval q = (people: Query[People, Person, Seq]).filter(

(p: People) =>

(

((p.age: Rep[Int]) < 5 || p.age > 65)

: Rep[Boolean]

)

)

Query marks collection-like query expressions, e.g. a whole table. People is the Slick Table subclass defined for table person. In this context it may be confusing that the value is used rather as a prototype for a row here. It has members of type Rep representing the individual columns. Expressions based on these columns result in other expressions of type Rep. Here we are using several Rep[Int] to compute a Rep[Boolean], which we are using as the filter expression. Internally, Slick builds a tree from this, which represents the operations and is used to produce the corresponding SQL code. We often call this process of building up expression trees encapsulated in place-holder values as lifting expressions, which is why we also call this query interface the lifted embedding in Slick.

It is important to note that Scala allows to be very type-safe here. E.g. Slick supports a method .substring for Rep[String] but not for Rep[Int]. This is impossible in Java and Java APIs like Criteria Queries, but possible in Scala using type-parameter based method extensions via implicits. This allows tools like the Scala compiler and IDEs to understand the code much more precisely and offer better checking and support.

A nice property of a Slick-like query language is that it can be used with Scala’s comprehension syntax, which is just Scala-builtin syntactic sugar for collections operations. The above example can alternatively be written as

sourcefor( p <- people if p.age < 5 || p.age > 65 ) yield p

Scala’s comprehension syntax looks much like SQL or ORM query languages. It however lacks syntactic support for some constructs like sorting and grouping, for which one has to use the method-based api, e.g.

source( for( p <- people if p.age < 5 || p.age > 65 ) yield p ).sortBy(_.name)

Despite the syntactic limitations, the comprehension syntax is convenient when dealing with multiple inner joins.

It is important to note that the problems of method-based query APIs like Criteria Queries described above are not a conceptual limitation of ORM query languages but merely an artifact of many ORMs being Java frameworks. In principle, Scala ORMs could offer a query language just like Slick’s and they should. Comfortably compositional queries allow for a high degree of code re-use. They seem to be Slick’s favorite feature for many developers.

Macro-based embeddings

Scala macros allow other approaches for embedding queries. They can be used to check queries embedded as Strings at compile time. They can also be used to translate Scala code written without Query and Rep place holder types to SQL. Both approaches are being prototyped and evaluated for Slick but are not ready for prime-time yet. There are other database libraries out there that already use macros for their query language.

Query granularity

With ORMs it is not uncommon to treat objects or complete rows as the smallest granularity when loading data. This is not necessarily a limitation of the frameworks, but a habit of using them. With Slick it is very much encouraged to only fetch the data you actually need. While you can map rows to classes with Slick, it is often more efficient to not use that feature, but to restrict your query to the data you actually need in that moment. If you only need a person’s name and age, just map to those and return them as a tuple.

sourcepeople.map(p => (p.name, p.age))

This allows you to be very precise about what data is actually transferred.

Read caching

Slick doesn’t cache query results. Working with Slick is like working with JDBC in this regard. Many ORMs come with read and write caches. Caches are side-effects. They can be hard to reason about. It can be tricky to manage cache consistency and lifetime.

sourcePeopleFinder.getById(5)

This call may be served from the database or from a cache. It is not clear at the call site what the performance is. With Slick it is very clear that executing a query leads to a database round trip and that Slick doesn’t interfere with member accesses on objects.

sourcedb.run(people.filter(_.id === 5).result)

Slick returns a consistent, immutable snapshot of a fraction of the database at that point in time. If you need consistency over multiple queries, use transactions.

Writes (and caching)

Writes in many ORMs require write caching to be performant.

sourceval person = PeopleFinder.getById(5)

person.name = "C. Vogt"

person.age = 12345

session.save

Here our hypothetical ORM records changes to the object and the .save method syncs back changes into the database in a single round trip rather than one per member. In Slick you would do the following instead:

sourceval personQuery = people.filter(_.id === 5)

personQuery.map(p => (p.name,p.age)).update("C. Vogt", 12345)

Slick embraces declarative transformations. Rather than modifying individual members of objects one after the other, you state all modifications at once and Slick creates a single database round trip from it without using a cache. New Slick users seem to be often confused by this syntax, but it is actually very neat. Slick unifies the syntax for queries, inserts, updates and deletes. Here personQuery is just a query. We could use it to fetch data. But instead, we can also use it to update the columns specified by the query. Or we can use it do delete the rows.

sourcepersonQuery.delete // deletes person with id 5

For inserts, we insert into the query, that resembles the whole table and can select individual columns in the same way.

sourcepeople.map(p => (p.name,p.age)) += ("S. Zeiger", 54321)

Relationships

ORMs usually provide built-in, hard-coded support for 1-to-many and many-to-many relationships. They can be set up centrally in the configuration. In SQL on the other hand you would specify them using joins in every single query. You have a lot of flexibility what you join and how. With Slick you get the best of both worlds. Slick queries are as flexible as SQL, but also compositional. You can store fragments like join conditions in central places and use language-level abstraction. Relationships of any sort are just one thing you can naturally abstract over like in any Scala code. There is no need for Slick to hard-code support for certain use cases. You can easily implement arbitrary use cases yourself, e.g. the common 1-n or n-n relationships or even relationships spanning over multiple tables, relationships with additional discriminators, polymorphic relationships, etc.

Here is an example for person and addresses.

sourceimplicit class PersonExtensions[C[_]](q: Query[People, Person, C]) {

// specify mapping of relationship to address

def withAddress = q.join(addresses).on(_.addressId === _.id)

}

val chrisQuery = people.filter(_.id === 2)

val stefanQuery = people.filter(_.id === 3)

val chrisWithAddress: Future[(Person, Address)] =

db.run(chrisQuery.withAddress.result.head)

val stefanWithAddress: Future[(Person, Address)] =

db.run(stefanQuery.withAddress.result.head)

A common question for new Slick users is how they can follow a relationship on a result. In an ORM you could do something like this:

sourceval chris: Person = PeopleFinder.getById(2)

val address: Address = chris.address

As explained earlier, Slick does not allow navigating the object-graph as if data was in memory, because of the problem that comes with it. Instead of navigating relationships on results you write new queries instead.

sourceval chrisQuery: Query[People,Person,Seq] = people.filter(_.id === 2)

val addressQuery: Query[Addresses,Address,Seq] = chrisQuery.withAddress.map(_._2)

val address = db.run(addressQuery.result.head)

If you leave out the optional type annotation and some intermediate vals it is very clean. And it is very clear where database round trips happen.

A variant of this question Slick new comers often ask is how they can do something like this in Slick:

sourcecase class Address( … )

case class Person( …, address: Address )

The problem is that this hard-codes that a Person requires an Address. It cannot be loaded without it. This doesn’t fit to Slick’s philosophy of giving you fine-grained control over what you load exactly. With Slick it is advised to map one table to a tuple or case class without them having object references to related objects. Instead you can write a function that joins two tables and returns them as a tuple or association case class instance, providing an association externally, not strongly tied one of the classes.

sourceval tupledJoin: Query[(People,Addresses),(Person,Address), Seq]

= people join addresses on (_.addressId === _.id)

case class PersonWithAddress(person: Person, address: Address)

val caseClassJoinResults = db.run(tupledJoin.result).map(_.map((PersonWithAddress.apply _).tupled))

An alternative approach is giving your classes Option-typed members referring to related objects, where None means that the related objects have not been loaded yet. However this is less type-safe than using a tuple or case class, because it cannot be statically checked, if the related object is loaded.

Modifying relationships

When manipulating relationships with ORMs you usually work on mutable collections of associated objects and inserts or remove related objects. Changes are written to the database immediately or recorded in a write cache and committed later. To avoid stateful caches and mutability, Slick handles relationship manipulations just like SQL - using foreign keys. Changing relationships means updating foreign key fields to new ids, just like updating any other field. As a bonus this allows establishing and removing associations with objects that have not been loaded into memory. Having their ids is sufficient.

Inheritance

Slick does not persist arbitrary object-graphs. It rather exposes the relational data model nicely integrated into Scala. As the relational schema doesn’t contain inheritance so doesn’t Slick. This can be unfamiliar at first. Usually inheritance can be simply replaced by relationships thinking along the lines of roles. Instead of foo is a bar think foo has role bar. As Slick allows query composition and abstraction, inheritance-like query-snippets can be easily implemented and put into functions for re-use. Slick doesn’t provide any out of the box but allows you to flexibly come up with the ones that match your problem and use them in your queries.

Code-generation

Many of the concepts described above can be abstracted over using Scala code to avoid repetition. There are cases however, where you reach the limits of Scala’s type system’s abstraction capabilities. Code generation offers a solution to this. Slick comes with a very flexible and fully customizable code generator, which can be used to avoid repetition in these cases. The code generator operates on the meta data of the database. Combine it with your own extra meta data if needed and use it to generate Slick types, relationship accessors, association classes, etc. For more info see our Scala Days 2014 talk at https://scala-slick.org/docs/.